Paul Cézanne (1839 –1906)

It is possible to say that the works of Cezanne represent at the same time a conclusion and, in a sense, a new point of departure. Cezanne concludes the 19th century formal developments initiated with Impressionism, and his “conclusion” is a somewhat paradoxical one.

Impressionism is indeed Cezanne’s starting point. And yet, the originality of his art comes from probing the limits of the aesthetics and the practice of Impressionism, pressing the boundaries of the style, touching the limits of the art form. Out of his efforts against the “dead ends” of the new art, out of the “impasse” of Late Impressionism, and by way of a kind of “reversal” of some of the central tenets of the Impressionist credo and praxis, Cezanne was able to produce original works that would point to new developments in the art of the early 20th century.

The art of Cezanne is in this sense, a “bridge” between the two centuries. Not so much in the letter, or the flesh of his style, although here also we can see a few seeds of future developments, but in the spirit of his quest, that is, in his demands for a new constructive or structural art.

In the early 20th century, Picasso and Braque, creating the new forms of Cubism, will see themselves as heirs to Cezanne. Distilled from Cezanne’s works, the geometric “reduction” of Cubism implied also the realization that the construction of a new pictorial language could not be separated from the production of a new pictorial matter, and therefore of a new objectivity of the work of art, a new art-object, expressing the new materiality of the new century.

Marcelo Guimaraes Lima

Paul Cézanne (1839–1906)

Impressionism is indeed Cezanne’s starting point. And yet, the originality of his art comes from probing the limits of the aesthetics and the practice of Impressionism, pressing the boundaries of the style, touching the limits of the art form. Out of his efforts against the “dead ends” of the new art, out of the “impasse” of Late Impressionism, and by way of a kind of “reversal” of some of the central tenets of the Impressionist credo and praxis, Cezanne was able to produce original works that would point to new developments in the art of the early 20th century.

The art of Cezanne is in this sense, a “bridge” between the two centuries. Not so much in the letter, or the flesh of his style, although here also we can see a few seeds of future developments, but in the spirit of his quest, that is, in his demands for a new constructive or structural art.

In the early 20th century, Picasso and Braque, creating the new forms of Cubism, will see themselves as heirs to Cezanne. Distilled from Cezanne’s works, the geometric “reduction” of Cubism implied also the realization that the construction of a new pictorial language could not be separated from the production of a new pictorial matter, and therefore of a new objectivity of the work of art, a new art-object, expressing the new materiality of the new century.

Marcelo Guimaraes Lima

Paul Cézanne (1839–1906)

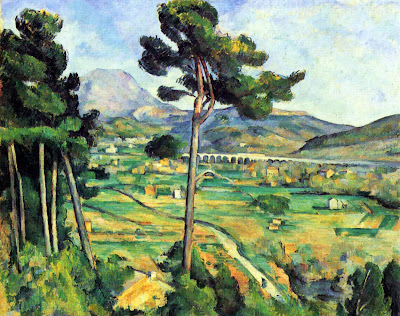

Mountain Sainte-Victoire1882-1885

Oil on canvas, 65,5 × 81,7 cm

Metropolitan Museum of Art

New York

Mountain Sainte-Victoire1882-1885

Oil on canvas, 65,5 × 81,7 cm

Metropolitan Museum of Art

New York

Paul Cézanne (1839–1906)

Mountain Sainte-Victoire, 1885-1887

Oil on canvas, 67 × 92 cm

Courtauld Institute Galleries

London

Mountain Sainte-Victoire, 1885-1887

Oil on canvas, 67 × 92 cm

Courtauld Institute Galleries

London

Paul Cézanne (1839–1906)

Road Before the Mountain Sainte-Victoire 1898-1902,

Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg

Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg

Comments