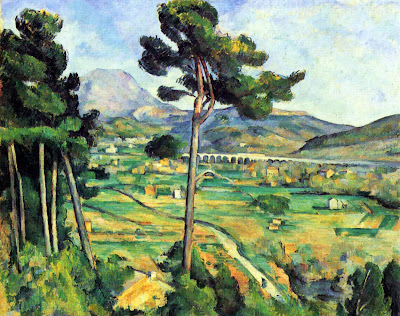

Les Demoiselles d´Avignon, 1907

Pablo Picasso

Les Demoiselles d´Avignon, 1907

Oil on canvas

243.9 cm × 233.7 cm (96 in × 92 in)

Museum of Modern Art.

Acquired through the Lillie P. Bliss Bequest, New York City

243.9 cm × 233.7 cm (96 in × 92 in)

Museum of Modern Art.

Acquired through the Lillie P. Bliss Bequest, New York City

The Demoiselles d´Avignon by Pablo Picasso, painted in 1907 and publicly exhibited for the first time in 1916, is a work made up of strong tensions, an image on the verge of disintegration, and yet held together by the very forces it brings forth in contradictory relationships, both at the thematic level and in its rather unexpected and unprecedented formal elements.

At the thematic level, the initial symbolic and narrative elements of sexuality and marginality, linking the painting to themes and moods previously explored by Picasso, are exacerbated to the point of dissolution of the painting’s thematic unity and framework. That process is concomitant with the formal disintegration of space and figures, and the progressive reworking of the human figure as the painter reconsiders and restructures the figurative elements into ever more urgent and angular forms.

Indeed form and space are deconstructed into triangular, cuneiform elements that interpenetrate, their hard edges and pointed forms cutting through implied surfaces, exploding the picture plane, blasting the represented surface and its elements as if also cutting through the actual surface of the painting in an intensified play of the ambiguities of figure and ground relationships.

The Demoiselles d’ Avignon is indeed a kind of narrative of displacements and of a severe and deliberate decentering process affecting not simply the artwork but the painter as well. With this painting Picasso deconstructs himself in a kind of cathartic experiment. He clears the ground for the radical shift of Cubism.

In one sense, Picasso’s Cubism can be said to be a response to the irruption of the Demoiselles d’ Avignon, an attempt to come to terms with its challenge, to rationalize the disturbing formal and emotional effects thereby produced, and to channelize the unconscious and subconscious energies and motifs that emerged from and with the artist’s radical gesture: the making and remaking of a painting that represented a remaking of painting itself.

The long interval between the production and the exhibition of the work shows that the Demoiselles was a painting that was able to “complete itself” after being abandoned by the artist in a state of formal and thematic “irresolution”. That “irresolution” will be the ground of a new art, the experimental, that is, the simultaneous constructive and deconstructive process of creating the artwork, will define the nature of art from now on.

At the thematic level, the initial symbolic and narrative elements of sexuality and marginality, linking the painting to themes and moods previously explored by Picasso, are exacerbated to the point of dissolution of the painting’s thematic unity and framework. That process is concomitant with the formal disintegration of space and figures, and the progressive reworking of the human figure as the painter reconsiders and restructures the figurative elements into ever more urgent and angular forms.

Indeed form and space are deconstructed into triangular, cuneiform elements that interpenetrate, their hard edges and pointed forms cutting through implied surfaces, exploding the picture plane, blasting the represented surface and its elements as if also cutting through the actual surface of the painting in an intensified play of the ambiguities of figure and ground relationships.

The Demoiselles d’ Avignon is indeed a kind of narrative of displacements and of a severe and deliberate decentering process affecting not simply the artwork but the painter as well. With this painting Picasso deconstructs himself in a kind of cathartic experiment. He clears the ground for the radical shift of Cubism.

In one sense, Picasso’s Cubism can be said to be a response to the irruption of the Demoiselles d’ Avignon, an attempt to come to terms with its challenge, to rationalize the disturbing formal and emotional effects thereby produced, and to channelize the unconscious and subconscious energies and motifs that emerged from and with the artist’s radical gesture: the making and remaking of a painting that represented a remaking of painting itself.

The long interval between the production and the exhibition of the work shows that the Demoiselles was a painting that was able to “complete itself” after being abandoned by the artist in a state of formal and thematic “irresolution”. That “irresolution” will be the ground of a new art, the experimental, that is, the simultaneous constructive and deconstructive process of creating the artwork, will define the nature of art from now on.

Marcelo Guimaraes Lima

Comments